Over the past five years, everyone could—and did!—make money in fintech investing. When valuations are skyrocketing, and seed to Series A graduation rates are approaching 100%, even the greenest investor can look like a genius. This up-and-to-the-right momentum obscured the fact that fintech investing differs in important ways from traditional technology investing. Successfully deploying capital in this sector requires knowledge born from deep domain experience, honed over many years through varying economic cycles—the ups, along with the downs.

At Foundation, we like to draw an analogy between locals and tourists to clarify how fintech investing stands apart. While locals appreciate the unique attributes and subtle nuances of financial services markets, tourists stumble in, enticed by the potential for outsize returns. These tourists inexpertly deploy capital, irrationally inflating valuations, then book the first flight home when markets revert.

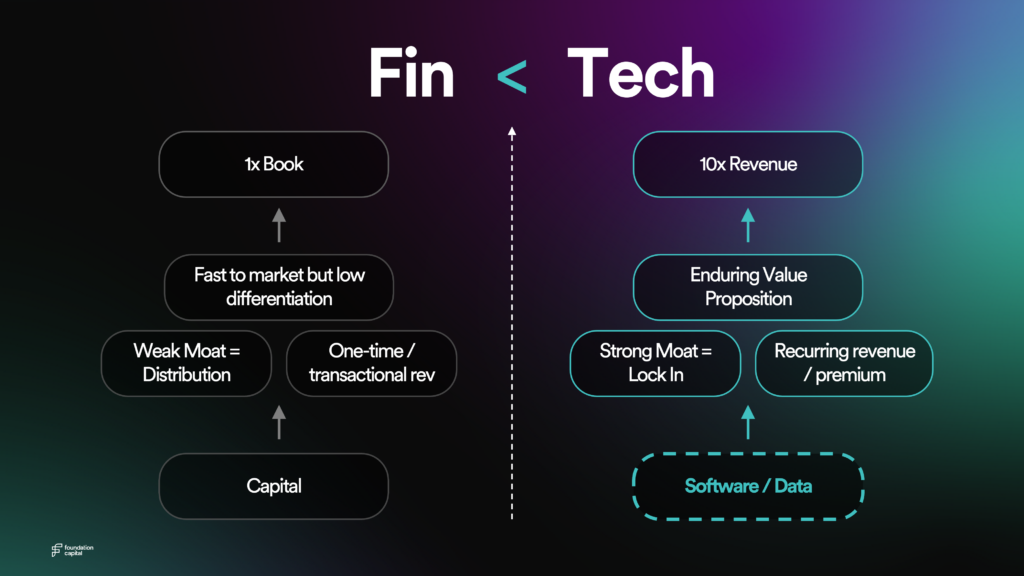

In this post, I unpack this analogy and describe six key lessons, understood only by locals, that orient our fintech team. Together, these lessons underline our topmost conviction that “tech” is greater than “fin.” Otherwise put: in the long run, fintechs that innovate on an underlying technology far outperform their peers that engineer novel financial products, absent any technological edge.

Avoiding the “Tourist Trap”

Consider the chart below, which shows the trading history of the Global X FinTech ETF—a rough barometer for the performance of fintechs worldwide, weighted toward the U.S.—since 2016. Prior to the most recent run-up, fintechs grew at a healthy CAGR of 15%. Then came the pandemic, which forced digitization and pushed the lion’s share of financial activity online. Buoyed by rapid user growth, heightened transaction volumes, and bullish expectations, fintech valuations rose to unsustainable levels.

During the innovation economy’s headlong tear from spring 2020 through fall 2021, investment in fintechs climbed over 2.5x, outpacing investments in other technology sectors by 25%. At peak exuberance, the median Series A fintech valuation was up 2.7x from one year prior, while the median Series B fintech valuation had risen more than 3.7x. We call this frothy period the fintech “tourist trap.”

Unsecured lender Upstart is a poster child for this irrational exuberance. The company traded as high as 38x revenue in fall 2021; it now trades at just 1.5x revenue. Similar stories can be told in the public markets about Affirm, Hippo, Root, and SoFi—the list goes on. Private markets were similarly roiled by ballooning valuations untethered to real business value. At the run-up’s height, neobank Chime was in talks to go public at a valuation of $35 to $45 billion with $950 million in run-rate revenue. Today, no date is set for its IPO.

Therein lies the root of my frustration as a fintech investor. When tourists reference the recent, staggering stock-price declines from formerly high-flying fintech IPOs, they tend to conclude that there’s a fundamental problem with the sector and that its dynamics thwart attractive returns.By contrast, locals discern that the market’s temporary, insatiable appetite for companies with no technological advantages and indefensible moats is the real culprit.

By investing in fundamentally sound companies at modest valuations at the earliest stages and projecting exit valuations at historical averages, fintech investors have repeatedly reaped venture-style returns. Recognizing the industry’s imprudent peaks for what they were—noise, not signal—our team’s median fintech entry valuation has barely budged since 2016.

Six Facts that Fintech Locals Know

In stressing the importance of a local’s knowledge, this post begs the question: why does expertise matter in fintech investing? The answer lies in the sector’s unique attributes: the nuances that only locals grok.

1. Fintech is not a monolith

Even after the recent correction, public financial services command a market cap in the trillions—yet it’s a gross oversimplification to suggest that a single type of business accounts for so much economic activity. A catchall term, financial services encompasses more than 30 subsectors which, despite all dealing in the business of money, have meaningful differences. Businesses as varied as regulatory technology (regtech) and payments, property technology (proptech) and capital markets, insurance technology (insurtech) and lending all live under a single moniker—not to mention the multiple sub-subsectors that each of these spaces contain!

Business models in financial services are similarly varied, from trading and AUM-based fees to transactional take rates and commercial MGA. Whereas enterprise software startups typically hew to a single business model, SaaS, whose key metrics (LTV to CAC, gross margin, net revenue retention, and so on) are clearly defined and readily comparable, fintech startups make use of over a dozen different options—some much more attractive than others.

Because of this dispersion, developing tested points of view about the relative merits of each permutation of fintech business type and fintech business model is critical. Key filters that our team applies include the sophistication of incumbents, the power of distributors, and the extent of regulatory risks, along with the offering’s capital intensity, its reliance on capital markets, and its ability to build sustainable advantage over the long term. Without the sharpened focus that these filters afford, fintech investors risk succumbing to hype and falling into the tourist trap.

2. Exit valuations depend on business models and moats

Within fintech, each permutation of business type and business model can trade at a vastly different exit valuation. Many (and I mean many) fintechs of the past decade were valued on ARR multiples at their Series A (and B, and C…) only to trade on book value once the public markets turned. Locals understand that knowing where a company will trade at exit is just as (and maybe even more!) important than haggling over the entry price.

3. Live by interest rates, die by interest rates

More than other technology sectors, fintech is highly sensitive to macro forces. When interest rates rise, economic growth slows, debt payments increase, and consumer credit weakens: all of which are bad news for consumer-facing fintechs. In recent years, many B2C fintechs (SoFi, Hippo, and Lemonade among them) have claimed online acquisition as their primary innovation: a fleeting advantage that rapidly erodes as CAC and pricing pressures from competitors mount. Specialty B2C lenders are particularly exposed to interest rate risk and suffer when once-plentiful streams of low-cost capital suddenly dry up. Sadly, many such companies now trade below their cash value in the public markets.

Rising rates also disproportionately impact fintechs whose largest direct expense is capital. In the “cash is trash” environment of 2008 through 2021, many fintechs relied on cheap, copious capital to scale, often very unprofitably. As rates have ticked up, these businesses have seen their revenues collapse. Indeed, as anyone who has studied for an investment banking interview knows, the Net Present Value formula punishes future cash flows exponentially relative to interest rates. The result: no-plans-to-be-profitable fintechs have been pummeled—even more so than cash-burning startups in other technology sectors.

4. Early traction can be ephemeral

Overweighting early fintech traction is one of the great downfalls of tourist investors. Consider two startups: Startup A, which sells enterprise security software to large corporations, and Startup B, a digital lender. Putting aside business model differences, let’s imagine both startups have exactly $1 million of revenue. For Startup A, and for investors more familiar with SaaS than fintech, this is cause for celebration! Although revenue is modest, one can assume that Startup A has built and launched a sufficiently complete, useful product such that someone, somewhere is willing to pay something for it.

On the other hand, with existing fintech infrastructure and sufficient capital, it’s relatively easy to spin up a neo-lending operation and start raking in the revenue—with fingers crossed that your customers will eventually pay you back. For Startup B, that $1 million of revenue is much easier to obtain than for Startup A. Locals recognize that, within some categories, early fintech traction provides a low—sometimes very low—ratio of signal to noise.

5. The best fintech founders have battle scars

The stereotypical entrepreneur is a [insert Stanford, M.I.T., or Harvard] dropout with zero business experience and empire-building ambitions. A different profile holds for fintech founders. In addition to insight and energy—a unique skill, idea, or appreciation for a thorny problem, together with the passion, enthusiasm, and resolve to solve it—fintech founders need a third, and equally critical, bona fide: experience. On the surface, fintech might seem like a straightforward place to innovate: just launch a bank and send people cards! Locals, however, grasp the power of experience. Even the simplest business models in fintech require interacting with a tangle of other entities like banks, custodians, payment networks, issuers, and compliance vendors—and probably more than one regulator to boot!

6. Regulation is mission critical

Which leads us to fintech locals’ sixth insight: navigating the regulatory maze is non-negotiable. While tourists treat regulation as a dirty word, locals embrace it as a day-one priority for any fintech startup. In 2020, there were over 50,000 financial services-related regulations in the U.S. alone: a number which, in the wake of banking meltdowns and crypto busts, is likely to soar in coming years. Fintechs whose primary play is regulatory arbitrage, absent any technological improvement to the status quo, will face increasing scrutiny. By pattern matching business types, business models, and founder traits with regulatory requirements and pitfalls, local fintech investors are uniquely able to support their portfolio companies.

“Tech” is Greater Than “Fin”

What does our awareness of these six facts mean, concretely, for our fintech investment strategy? It all boils down to realizing that, within fintech, “fin” is very different from “tech.”

“Fin” companies innovate on financial services using capital as their raw material. Yet, because capital is a commodity, “fin” fintechs struggle to build enduring moats. Most monetize through non-recurring, interest-rate dependent revenue streams. Due to the relative ease of getting started, these businesses are very often fast to market—which means copycats are never far behind. A prime example is Chime’s “Early Direct Deposit”: in effect, a short-term loan from Chime to its customers. The edge afforded by this feature was quickly competed away; today, early payday features are ubiquitous across neobanks and incumbents alike, from Credit Karma to Capital One.

“Tech” companies, by contrast, innovate on an underlying technology. Their core assets are software and data: paired building blocks whose value endures and deepens over time. “Tech” fintechs typically monetize through consistent, predictable revenue streams, which they sustain through their strong moats and the lock-in that ensues. Of course, more software means more investment and more time to get started. Yet the payoff is substantial: public markets reward “tech” fintechs with SaaS-like valuations based on multiples of revenue. Examples that we like include APIs that access financial data in interoperable ways; AI models that reduce fraud, automate cost centers, and improve underwriting and credit scoring; and blockchain-based solutions that power frictionless, global money movements.

At the core, it’s this propensity for software and data to upend incumbent dominance, either today or in the near future, that motivates all of our investments. Indeed, when we evaluate a startup, the first question we ask ourselves is: “Is this idea fundamentally ‘fin’ or ‘tech’?” For startups that fall in the second category, we apply the six lessons articulated above to identify the most promising opportunities. Each sits in the sweet spot where relatively low macro exposure meets high public trading multiples.

Stay Tuned!

In a forthcoming series of posts, we’ll dive deeper into the “tech” component of fintech and explore how advances in software, data, and machine learning are solving the toughest problems in financial services.

Published on 03.27.2023

Written by Charles Moldow